There are few legal options to see some of Ontario’s electrical generation infrastructure, especially historically significant ones. At the same time, you may still be able to take a public tour of the Sir Adam Beck Generating Station or get a glimpse at the RL Hearn station if you’re there for an event. But even in those, you are limited in what you can see unless you’re suitable for some casual trespassing. But when I learned that one of the iconic Niagara Falls generating stations was opening up as a tourist destination, I knew I had to check it out. So back in July, I finally had the chance to visit the goal, and it was well worth the wait.

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Power generation in the Niagara region is nothing new; the first plant opened not at the iconic falls but at DeCew Falls in St. Catharines in 1898, making it the oldest still operating generating station in the Province. But the potential of the iconic falls was seen when William B. Rankine formed the Niagara Falls Power Co in 1889, and in 1890 construction of a hydroelectric station on the American side of the river started. The Adams station began operation in 1895 and produced 2,200 kV AC power at 25Hz. We’re used to 60Hz power, but in the early days of electrical generation, there were no absolute standards, and power frequencies were all over the place. However, 25Hz became a favourite of industrial and commercial applications. The area was seeing an increase in industrial development. The Canadians saw this development and wanted to see the same power generation on their side of the river. So Rankine spun off the Canadian Niagara Power Co in 1892, with the promise of having an Adams’ type station running in Ontario by 1898. But the company over-promised and underdelivered. There were still plenty of bugs to work out, and construction would not start until 1901.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Konica-Minolta Zoom AF 17-35mm 1:2.8-4 D – Ilford Delta 3200 @ ASA-3200 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 12:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Konica-Minolta Zoom AF 17-35mm 1:2.8-4 D – Ilford Delta 3200 @ ASA-3200 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 12:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Konica-Minolta Zoom AF 17-35mm 1:2.8-4 D – Ilford Delta 3200 @ ASA-3200 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 12:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Konica-Minolta Zoom AF 17-35mm 1:2.8-4 D – Ilford Delta 3200 @ ASA-3200 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 12:45 @ 20C

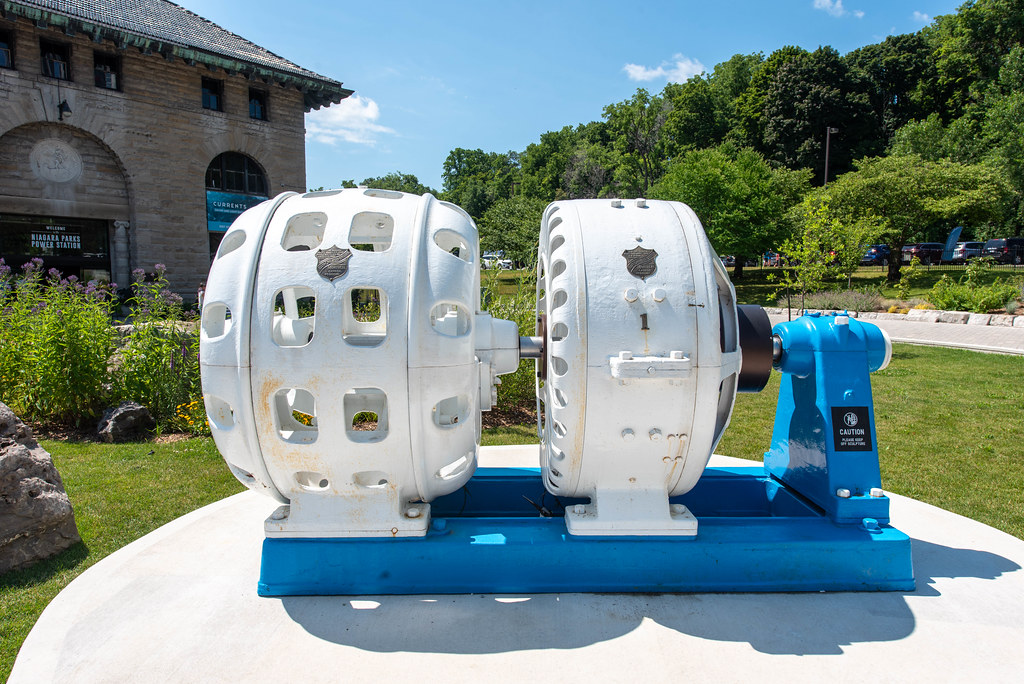

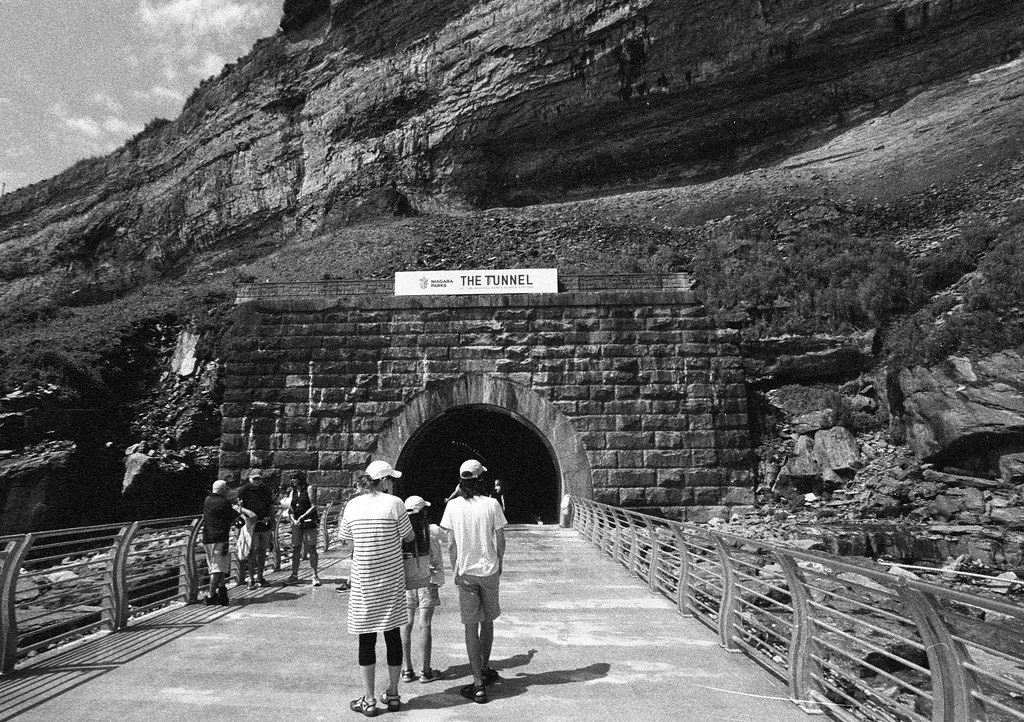

Construction moved slowly, as only limited heavy equipment was needed to aid the massive project. The coffer dam to hold back the Niagara River was first completed, allowing construction to commence on the massive 2200-foot tailrace and wheel pit. Construction of the tunnel lasted three years and finished in 1904, which allowed the main powerhouse to begin construction. Work on the wheel pit and penstocks moved slowly, so by 1905, only two generators could be installed in the still incomplete powerhouse. The plan was to have eleven such generators installed at Rankine. Each generator, designed by Nikola Tesla, produced 8,320kV of 25Hz AC Power; by 1910, six such generators had been installed, and the powerhouse was complete three years later. A transformer station was soon completed to help increase the power to allow for long-distance transmission (which had only been achieved in 1908). Rankine wouldn’t see full completion and maximum output until 1924, with the ability to produce 100MW of power but was limited to 76.4MW.

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

But even in the early 20th Century, more and more standardisation was starting to happen; even though 25Hz remained popular in industrial applications, the expansion of electrical lighting throughout the Province did not suit the 25Hz frequency well. The lightbulbs would noticeably flicker with the low frequency. Westinghouse tried to strike a balance with 50Hz power; 60hz seemed to be the sweet spot. In Europe, most went with the 50Hz standard; North America went with 60Hz. The transition was slow, and multiple generating frequencies were still found across the Province. The main push in Ontario came in the raft of cheap and affordable electrical devices to standardise the Ontario generating capacity to 60Hz. The commission discovered they still had 800,000 customers who used 25Hz power, so leaving some generating capacity of the utility frequency made sense. While the larger stations were upgraded to the standard frequency, Rankine was among those left to generate for industrial applications. But the economic downturn through the 1970s and 1990s began to end the 25Hz generation. By 2003 Rankine was only producing power-on-demand. And with the demand dwindling, the entire station was turned off in 2005. It wasn’t until 2008 that the final 25Hz station would be taken offline. Water rights for Rankine were redirected to the Niagara Tunnel project in 2009, and the property was turned over to the Niagara Parks Commission. Despite its age, the station was surprisingly intact, and work commenced in 2019 to convert the station to a museum, with the first phase opening in 2021 and the tunnel a year later.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Konica-Minolta Zoom AF 17-35mm 1:2.8-4 D – Ilford Delta 3200 @ ASA-3200 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 12:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Konica-Minolta Zoom AF 17-35mm 1:2.8-4 D – Ilford Delta 3200 @ ASA-3200 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 12:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Konica-Minolta Zoom AF 17-35mm 1:2.8-4 D – Ilford Delta 3200 @ ASA-3200 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 12:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Konica-Minolta Zoom AF 17-35mm 1:2.8-4 D – Ilford Delta 3200 @ ASA-3200 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 12:45 @ 20C

If you’re into industrial history or want to see one of the best views of Niagara Falls on the Canadian side of the river, the station is well worth the cost and the effort. As it is still a new attraction, it can get busy, so I highly recommend visiting early in the morning. The station opens at 10 am to try and get there for the opening and go straight down to the tunnel to have the view before touring the rest of the station. The tunnel is the full 2200 feet, far colder than when you’re above the falls, and it is damp. If you want to see all my images from the trip, you can visit the album over on Flickr and you can find details on how to purchase tickets over on the Niagara Parks website.

1 Comment