It was May 2009; I was on a road trip with three friends to explore the wealth of abandoned buildings up in Northern Ontario. Our previous night’s plans of camping out at a mine further north skunked by cold weather and the inability to hide our car safely. But that didn’t matter; we found a small motel on Highway 11 north of our next location, the town of Cobalt. Despite the name, the city once thrived with silver mines and started the northern Ontario silver rush that eventually butted into the gold rush further north. Silver from Ontario caused riots in New York City in the early 20th Century. Sadly I recently learned that this heritage is slowly collapsing due to vandalism and neglect. I figured I needed to walk those paths again, not physically but photographically.

Nikon D300 – Sigma DC 18-50mm 1:2.8 EX MACRO

Nikon D300 – Sigma DC 18-50mm 1:2.8 EX MACRO

Nikon D300 – Sigma DC 18-50mm 1:2.8 EX MACRO

The first settlers arrived in the area in the early 1880s. The first mineral strike that should come as no surprise was Cobalt. Discovered in 1884 by W.E. Logan, a mile south of the town of Haileybury. Silver wouldn’t be discovered for another two decades. The Temiskaming & Northern Ontario Railway (TNOR) construction was driving the railroad north from North Bay to Haileybury and New Liskeard, and the silver strike took place in 1903. Noah & Henry Timmins would be the first to establish a permanent settlement in the area, naming it Cobalt. Within a year, the place was swarming with prospectors coming from far and wide. And the silver was plentiful and close to the surface. By 1906, Cobalt was incorporated as a town, and in another two years, the town that was little more than a mining camp was considered the world’s largest silver and cobalt producer. By 1909 Cobalt housed some 10,000 people, all miners or connected to the silver industry. A fire ripped through the town that same year. The fire started in a downtown cafe, spread and destroyed half the town, some 150 buildings and left 3,000 residents homeless. But the town bounced back, buoyed by the silver still being pulled out of the ground. Some thirty-four mines produced 937.5 tons of silver by 1911. After the boom always comes a bust, as the easy to reach silver ran out, those who learned the trade moved further north with the siren call of gold. After the stock market crash of 1929, mining slowed to a trickle and ceased altogether in the 1930s.

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Mining interests renews in the mid-century following the Second World War; new technology and machinery allowed miners to go deeper into the earth to find more hidden riches. This only lasted a couple of decades before shutting down again in the 1980s. A second fire rushed through the town in 1977, caused by a discarded cigarette on a hot, windy day in May. Some 140 buildings were consumed, and 300 left homeless. In total, some 420 Million Ounces of Silver had been produced by Cobalt’s mines. Despite the silver mining shutting down, mineral exploration continues in the region today. Cobalt is a key component in the production of lithium batteries used extensively in mobile devices. And mining in Northern Ontario would prove far safer and stable than the Democratic Republic of Congo, which also presents tonnes of human rights questions. By 2017, deep earth diamond exploration continued operation, and several new cobalt interests were building in the region.

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

It’s amazing to think that much of the original mining done in Cobalt was all done by hand. Picks, wheelbarrows, and dynamite were the tools of the day. And sadly, there was little in the way of environmental production. Cobalt is not a healthy community environmentally. The entire lake was drained to allow easy access to the minerals found on the lake bed. Other lakes and rivers were used as dumps for waste rock, mill tailings, and plenty of arsenic. And this all is still present today, a century later. Heavy mining close to the surface has also left the area geologically unstable, with kilometres of shafts, trenches, pits, and tunnels covering the entire area. And while many are known, there are probably some that remain unknown and undocumented. At the same time, Cobalt did their best to capitalise on their position as Ontario’s most historic town and the home of hard rock mining in Canada, their position off the main highway (Highway 11) and the distance from any major population centre it difficult to visit. There are museums, a silver trail that highlights key points; these days, many are no longer present. Age, neglect, and vandalism have all taken their toll on the once rich town.

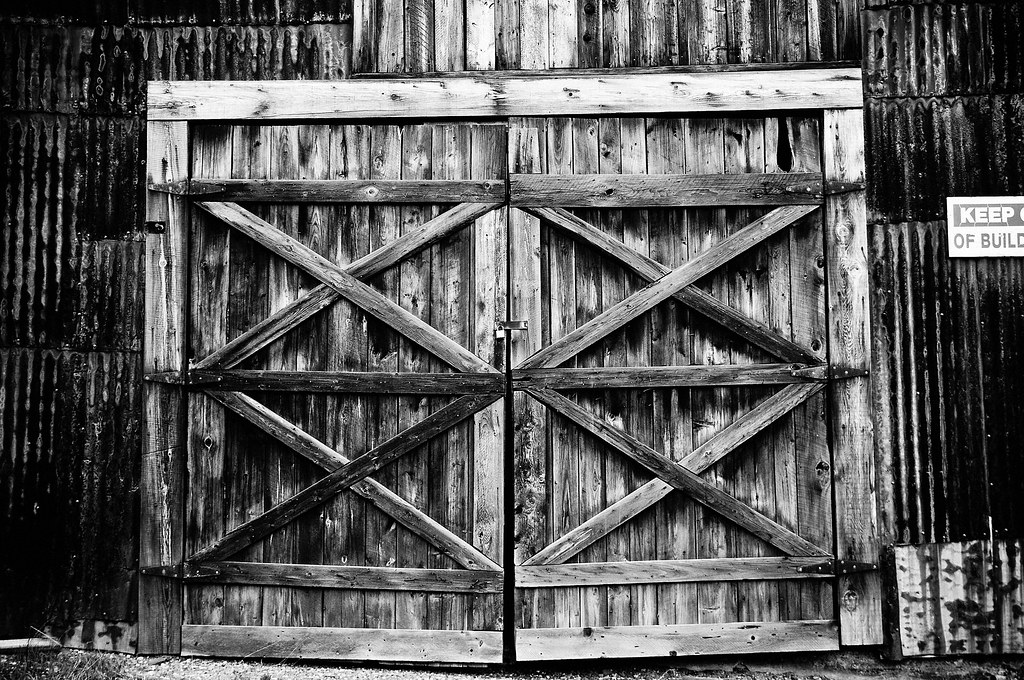

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Fujifilm Neopan Acros 100

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Fujifilm Neopan Acros 100

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Fujifilm Neopan Acros 100

The last time I visited Cobalt was back in 2011; even then, I noticed that many of the headframes that once dotted the landscape had fallen over the past two years. Sadly I have not been back since. Do I want to go back, strangely enough, I do. I’m still drawn to the area’s history. Plus, I would love to get my large format camera up into that area for the landscape and architectural details. And there are decent hotels up in that part of the world, at least out in New Liskeard and Dymond. Maybe one day, I’ll load up the car and head north again.