The western division of the British Forces in North America was in a tough spot, as was the Naval Squadron on Lake Erie. Both were starved for men, arms, and supplies. Despite several requests to their superiors, both Major-General Henry Proctor and Commodore Robert Barclay were forced to divide what little they had between them. For Proctor, the failure to dislodge or delay the army of Major-General William Henry Harrison by land left a rift between him and the Indigenous forces under the Shawnee leader Tecumseh. He had holed up at Fort Amherstburg and hung all his hopes on a naval victory on Lake Erie. Commodore Barclay had been forced to remove most of the heavy guns from Fort Amherstburg to arm his flagship, HM Ship Detroit, entirely and even filled out his crews with elements of the local militias and troops pressed into service from the Royal Newfoundland Regiment and 41st Regiment of Foot. Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry was in a similar situation; again, he was forced to work with what little had been sent from Lake Ontario and the eastern seaboard. And though some of the sailors he received did come from US Frigate Constitution, Perry is noted to have rated them poorly. Combined with new ships and crews, both commanders were forced into a fight neither wanted.

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

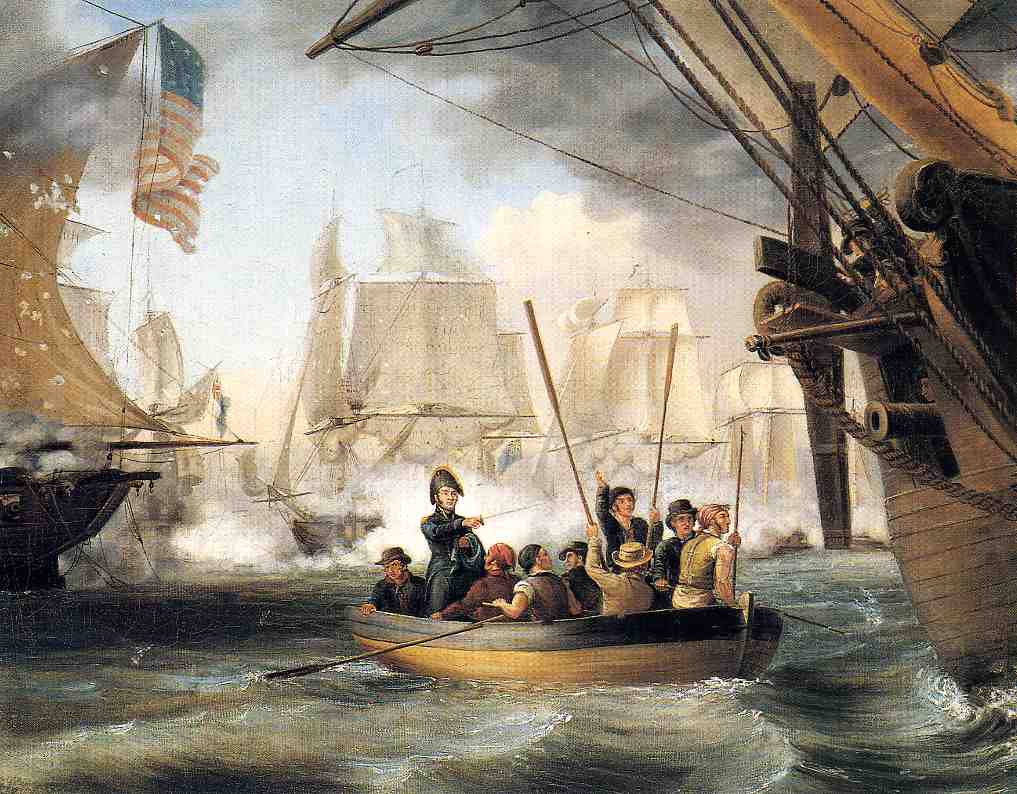

The two squadrons had two glaring differences, the first being armament. Perry armed his ships with close-range carronades, while Barclay focused on long-range guns. The second was that Perry only had two big ships: his flagship, the US Brig Lawrence, bearing his battle flag, emblazoned with the phrase “Don’t Give Up The Ship”, and the US Brig Niagara. He had several smaller schooners attached, but these were little more than gunboats, arming no more than four guns. Barclay had large ships, the two largest, a pair of ship-rigged sloops, his flagship Detroit and HM Ship Queen Charlotte, supported by a brig, sloop and schooner. On 10 September, the Royal Navy squadron sailed into view of Perry’s anchorage at Put-In-Bay, Ohio, a small island off the northern coast of Lake Erie. Perry ordered his squadron to sail immediately and planned to bring Lawrence and Niagara into close range; he would engage Detroit while Niagara took on Queen Charlotte, leaving the smaller schooners to engage their opposite numbers. The weather, however, was not in the American’s favour and allowed Barclay to close into the range of his long guns. Niagara had also held back, exposing Perry to the full force of the long guns from Detroit, Queen Charlotte, and HM Brig General Hunter. Lieutenant Jesse Elliot, commanding Niagara, was unwilling or unable to bring his ship in closer due to the poor handling of US Schooner Caledonia, which may have blocked his path. Despite the heavy fire, Perry continued to sail, being pounded the whole way. Then, after a good twenty minutes, his carronades were in range, but the guns had been overloaded and did little damage against the British ships. As the British continued their assault, Perry found himself in a ship with most of the crew dead and her guns out of action and had little choice. He ordered his flag taken down, but rather than surrender, he ordered himself rowed back a good kilometre, covered by a pair of schooners, to Niagara. He re-established his command there and ordered Elliot to return and bring the remaining schooners into action. The survivors of Lawrence quickly surrendered. The British had not escaped unscathed; Barclay had been wounded, as had many other officers as the two schooners next to Lawrence took on the British ships; command had been left to a Provincial Marine Lieutenant, who assumed that the Americans would choose to flee instead of counter-attack. But when Niagara and the remaining ships took advantage of the shift in the wind, they began to sail towards the Royal Navy Squadron. Commands were issued to bring the starboard batteries of Detroit and Queen Charlotte to bear. The damage to the ships and lack of wind caused the two ships to collide and their riggings entangled. Niagara, now with an easy target, moved in close and opened fire; both ships were shredded by American gunfire and by the time they had untangled, there was nothing left to fight with, and both quickly surrendered. The smaller ships made to escape, but soon, they were forced to strike their colours. Perry retook the Lawrence, and Commodore Barclay came aboard to surrender to Perry formally. We have met the enemy, and they are ours, penned Perry in his now famous dispatch to General Harrison. Perry had done the impossible: captured an entire British naval squadron and sailed everyone back to Presque Isle for repair, resupply, and refit.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X Pan @ ASA-320 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:30 @ 20C

Nikon FM2n AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.8 – Kodak Tmax 100 @ ASA-100 – Blazinal 1+50 12:00 @ 20C

Among the earliest goals of the American war plan was the capture of Montreal. Montreal was a major economic port and a key staging area for reinforcements from further east. The American capture of the city would cut off any hope of additional supplies and troops to the Upper Canada command. The goal was to capture the city between two armies, one commanded by Major General James Wilkinson and another under Major General Wade Hampton. The trouble was that neither general liked each other and would not accept commands from the other. To smooth things over, Secretary of War John Armstrong agreed that all communication would go through the War Department and to Wilkinson, he mentioned that Hampton would obey all orders. But for Wilkinson, things did not go smoothly; he was delayed in leaving Niagara and then again from Sacketts Harbor. General Hampton had sailed from Burlington, Vermont, to Plattsburg, New York, hoping to take a direct route north along Lake Champlain. His scouts, however, had warned of an increased British presence on Ile Aux Noix. Unwilling to commit to such a siege, Hampton chose to take a land route to establish headquarters south of the border with Lower Canada at Four Corners, New York. With his squadron repaired, rearmed, and reequipped, Perry sailed for Sandusky to embark on the invasion army of General Harrison. Harrison had intended to sail across Lake Erie. At the same time, a mounted militia force under Colonel Richard Johnson rode to recapture Detroit before crossing into Upper Canada. Even before Barclay had sailed, General Proctor planned to evacuate and retreat from Amherstburg, much to the anger of Tecumseh and the survivors of his confederation. On the same day that Harrison landed, Proctor completed the destruction of the fort and the navy yard and marched towards Burlington Heights. While the army marched on foot, much of the army’s ammunition sailed by bateaux along the Thames. Despite having the advantage, Harrison, who had captured the town unopposed, decided to secure the region before pursuing Proctor. Word spread quickly about Perry’s victory, and Commodore Chauncy wanted to repeat Perry’s victory on Lake Ontario. Chauncy knew he had the upper hand after launching his new flagship, US Corvette General Pike, and easily outclassed Commodore James Lucas Yeo’s flagship, HM Sloop Wolfe. Commodore Yeo was already on a massive ship-building campaign but had been sidetracked while supporting the reconstruction of a new fort at York and was busy ferrying men and supplies between Kingston and the capital. Chauncy’s squadron was spotted on 28 September. Rather than expose York to an American attack, Commodore Yeo made to sail for the nearest safe harbour, Burlington Bay. Yeo knew that he could not survive a stand-up fight against the Americans. The Americans could not survive against the guns of Burlington Heights. It proved to be a race for survival, and the two squadrons exchanged long-range fires against each other. Both ships managed to land shots against the other, and General Pike and Wolfe took damage. But as Yeo got in close to the entrance to Burlington Bay, he ordered the smaller ships ahead into the bay. He swung his ship around to bring his battery to bear and give Pike a broadside. Chauncy, spotting the manoeuvre, made to do the same. Each ship exploded with fire, landed blows, and took heavy damage. Commander William Mulcaster, aboard HM Sloop Royal George, spotting the flagship’s distress, manoeuvred between the two ships to continue the fight, and soon all the ships in both squadrons were engaged. As Yeo managed to limp into Burlington Bay, the other ships soon followed. Chauncy, though taking on water, was advised by Captain Arthur Sinclair to cut his losses, take a single British ship as the prize and return to Sacketts Harbor. Chauncy had little choice as he faced destruction at the hands of the British in one direction and by a storm in the other. He wisely returned to Sacketts Harbor to focus on building even larger ships.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 1:2.8 f=80mm – Fomapan 100 @ ASA-100 – LegacyPro Mic-X (1+1) 9:00 @ 20C (Constant Rotation)

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-200 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. E 6:30 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-200 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. E 6:30 @ 20C

On 2 October, General Harrison, along with regulars from the 27th US Infantry and a massive force of Kentucky militia, rode out in pursuit of General Proctor. The retreat for the British proved a miserable affair. General Proctor preferred to stay with the baggage train and his wife and left the remains of the 41st Regiment under Colonel Augustus Warburton. Proctor had done nothing to prevent or delay the pursuit by Harrison’s army. Roads remained unblocked, bridges intact, and signs were clear. Both Tecumseh and Roundhead spoiled for a fight at each spot. Still, Proctor declared it undefendable each time and ordered a further retreat. The bateaux lagged and were captured by Harrison’s advance forces, a fact unknown to Proctor. Upon arrival at the settlement of Chatham, Tecumseh and Roundhead felt this would be the best place to hold off the American advance. The Thames branched off to the main river and McGregor’s Creek; a small set of field fortifications was present and allowed for channelling the Americans into a killing zone with plenty of cover for irregular tactics. Proctor, however, ordered a further retreat but let a small group of Indigenous warriors destroy the bridge over the creek. When the advance force of the Americans arrived, the troops managed to destroy the bridge and deal a few casualties against the Americans. On 5 October, the miserable column was ordered a half-mile east, leaving their half-cooked and uneaten breakfast behind. Proctor intended to force Harrison to fight with his back to the Thames but lacked the firepower to force the issue; his lone six-pound gun lacked the needed ammunition. The Americans had captured the gun’s ammunition along with the bateaux. But Proctor would fight, and the 41st formed a loose line. The only support for the men came from Tecumseh, who rode along the line and acknowledged each soldier before joining his own on the right flank hidden in a swamp. Harrison ordered a combined charge by the mounted Kentucky militia, with the only response from the 41st being a pitiful volley before the line collapsed; some ran, and others made to fight and quickly surrendered. The Indigenous fought as if their lives depended on it, and the Kentucky militia took out all their pent-up anger against them; in the end, those who survived were slaughtered, and those who ran never came back. Both Tecumseh and Roundhead met their end in the fighting. Proctor had also run at first sight of the American charge but rallied the survivors at the Grand River near Brant’s Ford before continuing onto Burlington Heights. When Major-General Francis de Rottenburg learned of Proctor’s defeat and conduct, he stripped him of all commands, disbanded his division and ordered him arrested. Then, fearing a renewed American push, all troops were ordered to retreat from the Niagara region, and everyone was even made to roll up to Kingston. Only the word from General Vincent halted the retreat at Burlington Heights. In the east, the troubled attack on Montreal remained stalled. The two generals remained at odds with each other, and there was only so much that Secretary Armstrong could do; with supplies running low, Hampton had to retreat from Four Corners and was prepared to make winter quarters. But when word reached him that General Wilkinson had left Sacketts Harbor, he resupplied, returned to Four Corners, and began sending scouts across the border. Armstrong continued mediating communications between the two to ensure the attack happened before winter set in too deeply.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-200 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. E 6:30 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-200 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. E 6:30 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-200 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. E 6:30 @ 20C

The lateness of the year had made things miserable for the American troops encamped near the border. To make matters worse, Hampton now faced a dwindling army as many of his militia troops refused to cross the border into Lower Canada for many reasons, including lack of supplies, equipment, and the usual legal arguments against using militia troops to invade a foreign nation. There was also the matter that the border 200 years ago was not as quickly determined as it is today. In the backwater, both legal and illegal trade flourished. One of the American patrols happened across two brothers from the Manning family. Hampton had them arrested and then questioned while holding them in a stable at the farm where his army was camped. The brothers remained silent while Hampton boasted about the size of his army and plans to invade and take Montreal. Hampden even threatened to send the brothers to Greenbrush Prison, where many British prisoners of war were being held. When the General had exhausted himself and gotten nothing in return, he left, not knowing that the militia sergeant he had put in charge of the brothers was a friend who promptly let them go. The two men made tracks for the local military commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles de Salaberry. The colonel had a rough idea that an American army was nearby. The new information allowed him to plan a defense. He sent word of the invasion ahead to General Provost in Quebec City. The Governor immediately sent reinforcements from Quebec City in the form of Royal Marines. He ordered a group from the Select Embodied Militia to march to Montreal from Kingston. While de Salaberry had fewer troops than Hampton’s force, his command included the Canadian Voltigeurs, a specialised light infantry unit, the Canadian Regiment of Fencible Infantry, local mounted militia units and Mohawk troops. He set about destroying bridges, removing or changing local signs, and blocking roads. The goal was to funnel any invading force to the spot near the Chateauguey River, where de Salaberry had constructed a series of field fortifications to envelop and destroy the invaders. Patrols and mounted militia troops moved through the region, keeping de Salaberry informed of any movements. Hampton, however, remained unsure of Wilkinson’s movements, having heard nothing through the War Department or directly from Wilkinson. Not wanting any delay, he ordered Colonel Robert Purdy to cross into Lower Canada and push back any patrols or outposts encountered, clearing the way for the main body of troops to advance against the defenders. On the evening of 25 October, Purdy marched out of the American camp and into the darkness. The deep woods and efforts of the Canadians had confused Purdy. They would eventually cross the river and into Lower Canada. Making quick work of a mounted militia patrol, Purdy advanced on de Salaberry, but from an angle the colonel had not anticipated. He soon found the Americans on his flank. As Purdy engaged the Canadians in the early light, he sent word back to Hampden to move up and support his attack. The messenger arrived to find that the army had already marched off. General Hampton fell into de Salaberry’s trap, began deploying his troops into traditional lines, and ordered Brigadier-General George Izard to advance. The Americans traded smart volleys that smashed harmlessly against the fortifications that the Canadians hid behind and returned individual fire that picked out targets in the American lines. Bugle calls and war cries sounded in the woods as Mohawk and Militia troops rained in circles through clearings, making it appear that the Canadians had a much larger force. The Americans stood against the fire until Hampton and Izard realised they could not achieve victory and ordered a retreat. They expected Purdy to follow suit, but the messenger they sent to inform the colonel had gotten lost. Purdy’s troops were forced to fight back in New York under constant Canadian Patrol threats. General Hampton returned to find a message from Wilkinson to advance to Cornwall and capture the town; the General, now facing the growing threat of winter and a decimated force, sent a message ahead to Cornwall that he intended to make for winter quarters in Plattsburg and would not join him in Cornwall.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

General Wilkinson had high hopes for his army. When he sent word to General Hampton to meet him in Cornwall, his force had not even entered the St Lawrence River. They had only arrived at Grenadier Island on 1 November, almost inside the mouth of the river and entering Lake Ontario. The immense flotilla of American boats had not gone unnoticed, and a small force under Commander Mulcaster bombarded the American Camp near Clayton, New York. American artillery responded and set fire and sunk HM Schooner Moira. When Mulcaster returned to Kingston with the information, it was enough for General de Rottenburg to authorise a force under Colonel Joseph Morrison to observe the American movements, consisting of elements from the 89th and 49th Regiments. Commander Mulcaster would follow along with a small naval force to support the army. Wilkson travelled along the river quickly, even slipping past the guns of Fort Wellington in Prescott the day before Morrison arrived. They then landed an advance guard under Colonel Alexander McComb and Major Benjamin Forsyth to clear out any Canadian militia on the shores. The advance force made quick work of a small militia force at Point Iroquois before securing a campsite at Cook’s Point. When Morrison arrived at Prescott, he gathered additional troops from the Glengarry Light Infantry, Canadian Voltigeurs, Indigenous and the militia forces before advancing. Word of alarm spread along the St Lawrence Valley, and the arrival of a large American invasion force shattered the peace that had been in the region since early in the year. Militia forces quickly evacuated and removed military supplies from communities, including Cornwall, in fear of an American invasion and occupation. General Wilkinson set up his headquarters in Cook’s Tavern and called together his senior commanders. He ordered a force of Dragoons to move ahead to Cornwall and Major-General Jacob Brown to follow and occupy the town and await the arrival of General Hampton and then himself. He also learned of Colonel Morrison, who had advanced and camped at Chrysler’s Farm nearby. Rather than keep moving, he wanted to destroy the pursuing army and then push on despite learning of Hampton’s defeat. The morning of 11 November came with a cold mist, and American pickets began to engage their British opposites. Colonel Morrison felt the Americans were spoiling for a fight, and Wilkson thought the British were rattling the sabre. Both armies prepared for an attack. General Wilkinson, laid up due to illness, turned the command to Brigadier-General John Boyd to push the attack. The fighting remained sporadic through the morning, but by the early afternoon, a prominent American force began pushing the light troops back into the woods. Rather than press the advantage, they waited for reinforcements. The delay gave the British time to rally their forces to meet the American attack. When the rest of the Americans had formed and marched in, they were met by a combined British force and a disciplined volley of fire. One American commander, Brigadier-General Leonard Covington, is believed to have scoffed at a group of great coated soldiers, believing them to be militia and easily defeated. Only to march into the fire from the 49th Regiment of Foot and meet his end. Commander Mulcaster had begun bombarding the American camp, and the American artillery was about to come into action. The main force had been driven back, opening a route to take the guns. As the 49th Advanced, the 2nd US Dragoons came onto their flanks, forcing them to shift their fire and allowing the gun crews to escape, but the 89th was able to advance and capture the guns. Only the 25th US Infantry held fast, allowing the survivors to escape back to the boats and move along the river, preventing total defeat. Arriving in Cornwall on 12 November, the town was growing cold towards the American occupation. While generally civil, some looting had taken place, notably in the house of Reverend John Strachan; his family had taken shelter in Cornwall following the continued attacks against York. Wilkson also learned that Hampton had taken to winter quarters, decided to suspend the operations, and retreated to the United States.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

By: Lighbulbz, CC BY-SA 4.0

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

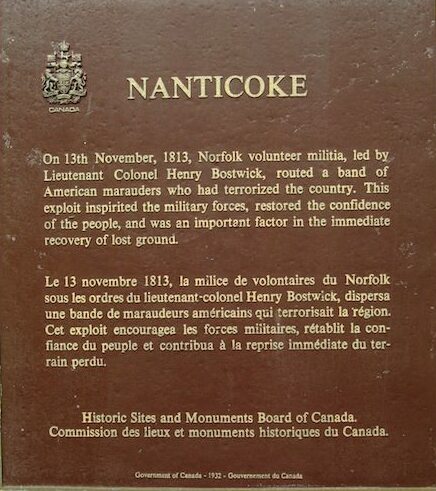

Despite chasing off the British to Burlington Heights and leaving a massive gap of no-man’s land in the western parts of Upper Canada, General Harrison did little to secure the area beyond the settlements along the Detroit River. This opened up the region to small raiding parties out of Amherstburg, local sympathisers, and from across Lake Erie, with only local militias operating to defend the territory as best they could. One such party from Buffalo began raiding through Norfolk and Haldimand Counties in mid-November. The raiders were aided in their mission by local sympathisers who often hid the Americans and the stolen goods. Farms and mills were stripped of flour, food, and clothing. Arms and ammunition were removed from armouries and caches in local government buildings, and loyal citizens and leaders were kidnapped and held for ransom. The population had taken enough and called a meeting of militia officers and community leaders at the house of William Drake. They all came to an agreement that something had to be done to remove the threat, and the militia agreed to launch a counter-raid to arrest or kill the raiders and arrest any sympathisers for treason. The one name that came up in the meeting was John Dunham, who lived in nearby Woodhouse Township, as a focal point for the American raids. On 12 November, the militia was alerted to the presence of Americans in the township. When the militia arrived, they had already fled to hiding. The next day, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Bostwick of the Oxford Militia led a force of Oxford and Norfolk Militia against the Dunham house. The home appeared abandoned, but not wanting to take chances, Colonel Bostwick deployed a company under Captain McCall to block the escape route to the lake and sent another company under Captain Bostwick around to the other side of the house. At the same time, he surrounded the rest of the property. Captain Bostwick, still not sure if there were people inside, took a lieutenant and burst into the house, finding it packed with Americans and their allies. Blustering, the captain demanded the occupants surrender and lay down their weapons. Most complied, but two opened fire, one hitting the captain in the face. On hearing the shot, the forces outside opened fire on the house, and a short firefight ensued. The raiders made it out the back and headed for the lake, only to run into Captain McCall, who made quick work and killed many. Upon seeing their comrade’s deaths, the remaining defenders quickly surrendered. Colonel Bostwick took five local citizens under arrest and marched them to Burlington Heights. Despite the unofficial nature of the action, many locals saw this as a major victory. They ensured the security of the local population and supplies.

Sony a6000 + SMC Pentax-A 1:4 200mm

Canadian Virtual Military Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 70-200mm 1:2.8G

The fall of 1813 had left Upper Canada preserved but bloodied. The summer’s victories had all but turned around and left two areas of the province open to American raiders, the one in the West and the Niagara region, with the Americans officially holding their small enclaves at Fort George and Amherstburg. In this vacuum, American sympathisers and raiders continued to operate. Most notably, in the Niagara region, the American authorities appointed Joseph Wilcox as the local sheriff. He used his position to harass local leaders and loyal citizens living under occupation. Wilcox would arrest the father of William Hamilton Merritt and use his irregular force of Canadian Volunteers to make life miserable. General de Rottenburg, as one of his last official acts as Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, authorises the acting attorney-general John Beverly Robinson to draw up a list of names of British citizens who allied themselves with the Americans and a list of charges that could be levelled against them. While the loss of the West cannot be entirely blamed on General Proctor, he would face stiff charges for his actions. Proctor would claim to have attempted to rally the men, but his officers and survivors would refute those claims. Proctor would be found guilty at a court marshal and be suspended without pay, and the charges and verdict would be read to every regiment in the British Army by the order of Prince Reagent (the future King George IV). Although these charges would be commuted and reduced to a reprimand, Proctor never again held a command and quietly retired back to Great Britain. As winter settled in, the unpopular de Rottenburg would be removed by General Prevost and returned to Lower Canada to command the garrison at Montreal and a new Lieutenant-Governor was appointed, Major-General Gordon Drummond, born in Lower Canada and full of fire and ready to take a more direct approach to the war.

Canon EOS 3000 – Canon Lens EF 28-80mm 1:3.5-5.6 II – Arista EDU.Ultra 200 @ ASA-200 – Ilford Perceptol (1+1) 7:30 @ 20C

Painted by George Theodore Berthon (1806-1892), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

A memorial in Perry Square in downtown Erie, Pennsylvania, to Oliver Hazard Perry in the form of a statue can be found; you can also find a memorial column at Presque Isle. But probably the most notable item you can visit and even see is the restored US Brig Niagara, the ship that sails today is a 1988 reconstruction that contains some elements of the original Brig although it is mostly modern making it a bit of a Ship of Theseus. One of the captured sloops from Barcley’s squadron entered the US Navy as US Sloop Little Belt (originally US Sloop Friends of Goodwill, then HM Sloop Little Belt); today, you can visit a modern reconstruction of the Little Belt as the Friends of Good Will at the Michigan Maritime Museum in South Haven, Michigan. Two plaques remember the Burlington Races; one is located in Harvey Park near Dundurn Castle in Hamilton, Ontario and a second, more detailed plaque is located in Spencer Smith Park in Burlington, Ontario. The historical society in Chatham-Kent has constructed a historic parkway route, the Tecumseh Parkway, that runs from Tecumseh Memorial Park in downtown Chatham-Kent to the original battlefield located on Longwoods Road (Old Highway Two). The battlefield also contains a memorial to the Shawnee Chief and two historical plaques, one in English and French and a second in Anishinaabemowin. Further along is the Fairfield Museum, located on the original site of Moraviantown. The settlement was rebuilt and remains part of the sovereign Delaware Nation. Parks Canada operates the Châteauguay Battlefield as a national historic site. It has a small visitor centre, and about five minutes away is the 1895 memorial Obelisk in Howick, Quebec. The former Chrysler’s Farm battlefield was also made a national historic site, and a memorial obelisk was erected in 1895. The construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway flooded the site in the 1950s. Thankfully, a section of the battlefield and the memorial were relocated to Upper Canada Village in Morrisburg, Ontario. The dirt turned into a memorial mound with a small museum underneath the memorial atop the mount. In the village is the former Cook’s Tavern (rebuilt in 1820) that served as the American headquarters, and some buildings may have also been present during the battle. The city of Cornwall has several plaques around the town related to the brief American occupation. A plaque related to the skirmish present is located in the Nanticoke Community Centre. Interestingly enough, the veterans of the battles of the Châteauguay and Chrysler’s Farm were allowed to apply to receive the Military General Service Medal in 1847 and were two of three 1812 battles that were allowed, the other being the capture of Detroit.